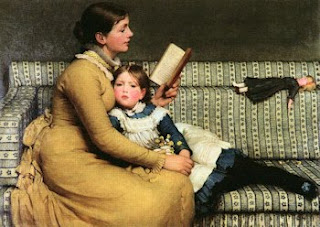

Alice in Wonderland, George Dunlop Leslie

Love Alice's chubby and serious little face, the couch, her resting doll, her mama's yellow dress, her black tights and shiny shoes, the way her pinafore is falling off one shoulder, and that she's being read to. Alice is so vulnerable in Wonderland that I like to think of her here, although I guess the title implies that this is sort of a Wonderland, too. Maybe the Wonderland, come from a book.

(Should say, saw it first here, at a blog I am certainly obsessed with as well.)

Showing posts with label art. Show all posts

Showing posts with label art. Show all posts

Friday, May 21, 2010

Tuesday, January 6, 2009

If Bees Made the Clouds, Clouds Would Rain Honey

Sam and I saw a Tara Donavon exhibit this weekend at the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Art).

Sam and I saw a Tara Donavon exhibit this weekend at the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Art). First a word on the ICA: We got engaged there, we just didn't know it. It's right on the harbor, right next to Anthony's Pier Four, the fancy restaurant where Sam bought us a four pound, 50-year-old lobster, which actually didn't give me a clue that he wanted to ask me any important questions. Neither did him insisting we stand in front of the ICA (which I thought was just a weird office building) and look out at the water for a little while. I didn't get it until he dropped to BOTH knees, and asked. And for the record, because he'll correct me in my comments again if I'm not accurate with the dialogue, I said "I hope so," then a guy walking out of the ICA said, "Just say Yes!" so I said "Yes," and then I said, "I don't know, I have to think about it." Poor man. I would proceed to say yes, then I don't know, then yes over the course of three weeks. I tried his love.

Anyway, enough love.

I LOVE the Tara Donovan stuff we saw. Click on her name for a whole bunch of photos of her stuff. It is beauty. It's mostly installation art, made from everyday commercial objects in mass quantities: drinking straws, Styrofoam cups, tooth picks, scotch tape, glue. You would be SHOCKED at how lovely that stuff can be, how much it can look like elements of the natural world.

Take this, for example. Styrofoam cups. I think it looks like clouds, if bees were assigned to make them. Sam thought it looked like coral. Either way, both of us stood underneath it, our mouths agape, astounded and lost in it, pointing to beautiful curves.

This, paper plates. Yes, I know.

Toothpicks, held together with nothing.

And buttons. Did you know buttons could be so pretty? They remind me of The Little Mermaid's castle.

Sunday, January 4, 2009

On How a Mormon Reads Lolita

I read Lolita over Christmas break, and found it to be one of the most heartbreaking, beautiful books I've ever read.

It makes me nervous to admit this, admit I read it. It's one of those books you hear whispers about before you ever read it, especially when you're a good little Mormon girl, as I am/was/will forever be. (As a sidenote, check out this article on a kid's bed misguidedly named, "Lolita Bed." So not cool.)

You see, Mormon folk are careful what they read/watch/see. When I was growing up, I wasn't allowed to watch PG-13 movies, and I remember trying to read a book by Joyce Carol Oates and feeling like God told me not to read it anymore. Which, I sort of think He did, because it was ugly and negative and boring. So I grew up thinking that there was such a think as "moral" literature, books we "should" read and books we should not. And I still suspect that's true, I just don't know what they are anymore. The line seems blurry.

Take Lolita: the main character is Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who is basically a pedophile, who seduces (or is seduced by, some critics say) a 12-year-old girl. Do I find the thought of this character disturbing/disgusting? Yes, yes I do. Take him out the walls of literature, and I hate him, I say lock him up; tell me he lives on my street and I'll move to another neighborhood to protect my kids. I think about my niece who is nearly twelve and I just shiver.

But the book tells this man's story, and makes you feels stuff about him, stuff for him. At the end I wept for him, this man. I find I'm sort of offended when I (or someone else) boils the plot down and calls him a pedophile. And so maybe the book, therefore, is "bad." Do we really need books that redeem pedophiles?

That's one way to see it. The other way takes me to something C.S. Lewis said:

"[I]n reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do."

There's more to it than that, but I can't find it. He says something about wishing the dung beetle could write books, because he'd want to read those too. And Humbert is a dung beetle; he basically says so himself.

Nabokov, in a essay at the back of my edition, talks about the seed for the book. He says he felt the first stirrings of it when he read in the paper about an ape they taught to draw, and how they painstakingly, over months and months, tried to teach it, and when they finally succeeded, what it drew were the bars of its cage. What's the implication here, the connection to Lolita? Humbert is writing the book from prison, so I assume the book is, in a way, the bars of his cage. And it feels like the bars of the cage. As I said, it's heartbreaking.

So maybe it's like something Yeats says, in a book of essays I can't remember the title of. He argues that literature is the purest Christlike act, because in a sense we do as Christ did, forgive, redeem. We take something dispicable and are made to understand it, to see the man as a man, not just a sinner who should be locked up. Which is how Christ sees us, right, with love no matter what we've done? I was talking about this with Sam, trying to figure it out, and I asked him if there was ever a limit what we should forgive, if there are people we simply should not read/write books about, and he said, "I don't know. Not according to Jesus." Point taken.

And there is a barrier between art and life, and of course this doesn't apply in the courtroom because laws against pedophila and murder are important and meant to keep us safe and maintain order. And Nabokov never says the bars of Humbert's cage shouldn't be there, he just shows you what they are.

And still, I'm nervous. Isn't there a limit, a line, a point we shouldn't cross? Or maybe all the lines are personal, none superior to the other?

Two sides, and I find myself straddling them. Do I want my nieces/nephews/future children reading Lolita? Maybe in a long long while. If I met my twelve or even twenty-year-old self, would I recommend the book to her? No, no I wouldn't. I wouldn't have been ready for it yet.

But now, I love it. At the end, when Humbert is driving down the wrong side of the road, and they put up a roadblock and pull his despairing, limp, apathetic body from his car, I wasn't sorry I read. Oh, I wasn't.

It makes me nervous to admit this, admit I read it. It's one of those books you hear whispers about before you ever read it, especially when you're a good little Mormon girl, as I am/was/will forever be. (As a sidenote, check out this article on a kid's bed misguidedly named, "Lolita Bed." So not cool.)

You see, Mormon folk are careful what they read/watch/see. When I was growing up, I wasn't allowed to watch PG-13 movies, and I remember trying to read a book by Joyce Carol Oates and feeling like God told me not to read it anymore. Which, I sort of think He did, because it was ugly and negative and boring. So I grew up thinking that there was such a think as "moral" literature, books we "should" read and books we should not. And I still suspect that's true, I just don't know what they are anymore. The line seems blurry.

Take Lolita: the main character is Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who is basically a pedophile, who seduces (or is seduced by, some critics say) a 12-year-old girl. Do I find the thought of this character disturbing/disgusting? Yes, yes I do. Take him out the walls of literature, and I hate him, I say lock him up; tell me he lives on my street and I'll move to another neighborhood to protect my kids. I think about my niece who is nearly twelve and I just shiver.

But the book tells this man's story, and makes you feels stuff about him, stuff for him. At the end I wept for him, this man. I find I'm sort of offended when I (or someone else) boils the plot down and calls him a pedophile. And so maybe the book, therefore, is "bad." Do we really need books that redeem pedophiles?

That's one way to see it. The other way takes me to something C.S. Lewis said:

"[I]n reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do."

There's more to it than that, but I can't find it. He says something about wishing the dung beetle could write books, because he'd want to read those too. And Humbert is a dung beetle; he basically says so himself.

Nabokov, in a essay at the back of my edition, talks about the seed for the book. He says he felt the first stirrings of it when he read in the paper about an ape they taught to draw, and how they painstakingly, over months and months, tried to teach it, and when they finally succeeded, what it drew were the bars of its cage. What's the implication here, the connection to Lolita? Humbert is writing the book from prison, so I assume the book is, in a way, the bars of his cage. And it feels like the bars of the cage. As I said, it's heartbreaking.

So maybe it's like something Yeats says, in a book of essays I can't remember the title of. He argues that literature is the purest Christlike act, because in a sense we do as Christ did, forgive, redeem. We take something dispicable and are made to understand it, to see the man as a man, not just a sinner who should be locked up. Which is how Christ sees us, right, with love no matter what we've done? I was talking about this with Sam, trying to figure it out, and I asked him if there was ever a limit what we should forgive, if there are people we simply should not read/write books about, and he said, "I don't know. Not according to Jesus." Point taken.

And there is a barrier between art and life, and of course this doesn't apply in the courtroom because laws against pedophila and murder are important and meant to keep us safe and maintain order. And Nabokov never says the bars of Humbert's cage shouldn't be there, he just shows you what they are.

And still, I'm nervous. Isn't there a limit, a line, a point we shouldn't cross? Or maybe all the lines are personal, none superior to the other?

Two sides, and I find myself straddling them. Do I want my nieces/nephews/future children reading Lolita? Maybe in a long long while. If I met my twelve or even twenty-year-old self, would I recommend the book to her? No, no I wouldn't. I wouldn't have been ready for it yet.

But now, I love it. At the end, when Humbert is driving down the wrong side of the road, and they put up a roadblock and pull his despairing, limp, apathetic body from his car, I wasn't sorry I read. Oh, I wasn't.

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Art

Was thinking today about the creation of the world--the classic story: organizing matter, dividing light from darkness, land from sea, making animals and plants, and finally man and woman.

And it occurred to me: God didn't make art. He designed the centipede, arranged the perfect tendons in my right hand, piled big rocks to make Kilimanjaro, gouged the Grand Canyon. But He didn't set down music, painting, and the novel on the planet. We did that.

Don't get me wrong, I think God has a lot to do with the creation of art, just as He's behind advances in science and technology. I'm of the opinion that good stuff comes from Him. My most successful work seems to come from some place beyond me.

But it struck me: art, as such, is so purely and beautifully human. It's our chance to create, to make something from nothing, to organize matter, to create the world.

And it occurred to me: God didn't make art. He designed the centipede, arranged the perfect tendons in my right hand, piled big rocks to make Kilimanjaro, gouged the Grand Canyon. But He didn't set down music, painting, and the novel on the planet. We did that.

Don't get me wrong, I think God has a lot to do with the creation of art, just as He's behind advances in science and technology. I'm of the opinion that good stuff comes from Him. My most successful work seems to come from some place beyond me.

But it struck me: art, as such, is so purely and beautifully human. It's our chance to create, to make something from nothing, to organize matter, to create the world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)